Summary

- Introduction

- Chatbot use in consumer finance

- Exclusive industry insights

- Use of large language models and AI

- Growth and adoption in the financial industry

- Problems consumers encountered while engaging with chatbots

- Technical limitations and associated security risks

- The perils of implementing flawed chatbots

- Conclusion

Introduction

Chatbots are computer programs that simulate human interaction by interpreting user input and returning the desired result. Rule-based chatbots launch predetermined, constrained answers using either decision tree logic or a database of keywords. These chatbots may provide the user with a prepared menu of choices to choose from or guide the user between alternatives based on a specified set of keywords. More advanced chatbots employ other technologies to produce answers. Chatbots have been extensively embraced by banks, mortgage servicers, and debt collectors.

Access to the correct data at the right time can make a difference between millions in profit and millions in loss in a data-rich industry. According to the report by Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB), financial institutions are using chatbots more frequently to cut down on the costs of hiring human customer service representatives. They are also moving away from basic, rules-based chatbots and towards more complex technologies like large language models, generative chatbots, and other tools dubbed artificial intelligence (AI).

Chatbots may be helpful for providing simple answers, but as queries become more complicated, their usefulness decreases. The CFPB warns that financial institutions run the risk of breaking federal consumer protection law when implementing chatbot technology because a review of consumer complaints and of the current market shows that some people experience significant negative outcomes due to the technical limitations of chatbot functionality.

Read: Trust in Banking Explained With 10 Live Examples

Customers’ faith in a business might be severely damaged if chatbots are badly made or if they can’t receive help when they need it. Potential breaches in confidentiality and safety are among these threats. In particular, these chatbots may be programmed to use machine learning or technology sometimes marketed as “artificial intelligence” to mimic human dialogue.

Over 98 million customers engaged with a bank’s chatbot in 2022, and it is anticipated that this figure would rise to 110.9 million users by 2026.

Read the latest article: 10 Best Applications Of AI In Banking

Chatbot use in consumer finance

Financial institutions have historically interacted with both potential and current consumers via a range of methods. The purpose of bank branches is to provide clients with a location close to their homes where they can perform banking transactions and get customer care and support. Relationship banking has long placed a premium on having face-to-face interactions with financial institutions.

Financial institutions have gradually expanded their contact centers previously known as call centers to enable clients to communicate with their institutions more conveniently. As these organizations expanded, a lot of their contact center operations turned to interactive voice response (IVR) technology in order to route calls to the proper parties and save expenses.

The introduction of chat in consumer finance allowed customers to have real-time, back-and-forth interactions over a chat platform with customer service agents. Financial institutions deployed online interfaces for customer support as new technology became available, such as mobile applications, the ability to send and receive messages, or through “live chat.”

The introduction of chatbots, which mimic human replies via computer programming, was mostly done to save the price of hiring actual customer support representatives. In order to automatically generate chat responses using text and voices, financial institutions have recently started experimenting with generative machine learning and other underlying technologies like neural networks and natural language processing. Below, we describe the use of chatbots for customer support.

The technology used as a foundation, such as extensive language models and “artificial intelligence”

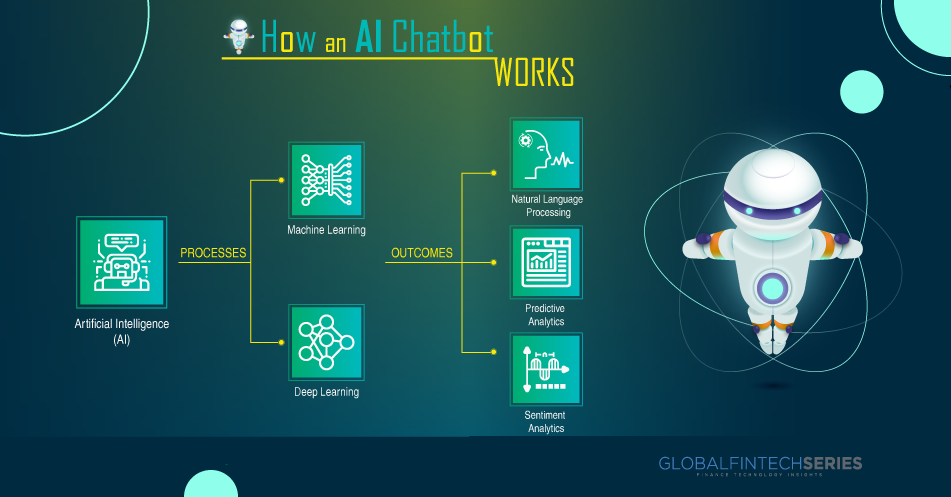

Computer programs called chatbots imitate some aspects of human speech. They all take user input and employ programming to create an output, despite the fact that they might differ greatly in terms of complexity, automation, and features.

Read: Unleashing The Power: How Tech Giants Harness Generative AI Chatbots

Rule-based chatbots launch predetermined, constrained answers using either decision tree logic or a database of keywords. These chatbots can provide responses depending on established criteria, such as providing the user with a prepared menu of possibilities to choose from or guiding the user between options based on a specified set of keywords. The user is often restricted to specified inputs. For instance, a bank chatbot may provide the customer with a predetermined selection of alternatives, such as checking their account balance or making a payment.

More advanced chatbots create replies using different technologies. These chatbots may be created to mimic natural conversation using machine learning or other software frequently referred to as “artificial intelligence” (AI). More sophisticated chatbots use LLMs to examine word patterns in large datasets and predict the text that will be used to answer a user’s question.

Exclusive industry insights

Exclusive insights by Dan Adamson CEO of Armilla AI, a company that provides AI validation and development tools to create responsible and robust AI, including AutoAlign, a tool that provides safeguards for generative AI.

The Evolution of Chatbots for Consumer Finance

Chatbots are set to become more prevalent, more powerful, and potentially more dangerous in consumer banking. The biggest banks in America are all now using chatbots for customer service, with an estimated 37% of consumers having engaged them. However, these chatbots are rather “basic” in both scope and intelligence. Most are largely rules-based, with some limited AI integrated (for example, to increase coverage by parsing questions into root types of questions, for example).

Unless you have been living under a rock, you have probably seen much more sophisticated chatbots such as ChatGPT, or Google’s Bard, or Microsoft’s Bing Chat (powered by GPT) that can handle much more complicated queries and have much more intelligent conversational capabilities. These systems are “Large Language Models” (LLMs) and are part of a new powerful class of generative AI. These systems could also be a very powerful tool for consumers: imaging the chat interface becoming the primary interface for interacting with your bank:

“Based on my upcoming bills and credit card billing cycle, can I afford to buy this $400 jacket now or should I wait?”

We can also imagine chatbots connected to other services:

“Look for 2 tickets to tonight’s Yankee’s game in the upper section, and buy them if I have enough room credit on my card.”

While these chatbots could start to get very powerful, there are a number of risks around chatbots, and these will only get worse with the next-generation of chatbots. Even the CFPB is warning of the dangers. For this next generation of chatbots, some older best practices will become even more critical: for example, it will become very hard to tell a chatbot from a human, so the bank will always really need to make it clear to their user that they are, in fact, talking to a bot.

However, builders of these more advanced chatbots will also need to be very careful in new ways, before these new chatbots can be deployed. These new models can be very convincing at making things up (“hallucinating”), and can also change their tone and suddenly be rude to customers. They can also exacerbate biases or be ‘jailbreaked’ to make harmful statements.

Luckily, there are also technologies emerging to protect against these risks – for example AutoAlign, can help automate testing and fine-tuning of these models, and can provide guardrails to reduce biases, hallucinations and jailbreaking.

It will be interesting to see how quickly financial institutions can roll out this new next generation of chatbots and what it means for consumers – hopefully the right balance can be struck where chatbots become more useful while not creating new harms.

Read: How Can Banks Stay Competitive With A Secured IT Security Infrastructure?

Use of large language models and AI

Chatbots are software applications that attempt to simulate human dialogue. All of these systems take in user input and process it according to predetermined guidelines in order to generate an output; nevertheless, they can vary widely in terms of complexity, automation, and features.

Read: A Global Map Of Cryptocurrency Regulations

The predetermined, limited responses of rule-based chatbots are triggered by either a decision tree logic or a database of keywords. These chatbots can either provide the user with a prepared list of options to choose from or guide them through the available choices based on a specified set of keywords and predetermined rules. In most cases, the user’s choices for input are severely restricted.A chatbot provided by a financial institution may present the user with a limited amount of alternatives, such as viewing the account balance or making a payment.

Additional technologies are used by more advanced chatbots to generate responses. Machine learning and other forms of so-called “artificial intelligence” could be incorporated into the design of such chatbots in order to better mimic human conversation. LLMs are also used by more advanced chatbots to examine the relationships between words in vast datasets and make predictions about the best course of action when responding to a user’s query.

Domain-specific chatbots, such those designed for the healthcare, academic, and financial sectors, are focused on assisting users with narrower goals.The financial sector is the primary focus of our investigation.

Growth and adoption in the financial industry

In the financial sector, chatbots are prominently displayed on websites, smartphone apps, and social media pages of banks, mortgage servicers, debt collectors, and other financial firms. Over 98 million people, or over 37% of the US population, interacted with a bank’s chatbot in 2022-23. By 2026, this figure is anticipated to reach 110.9 million users.

Notably, the top 10 commercial banks in the nation all engage consumers using chatbots of differing levels of sophistication. These chatbots may sometimes be given human identities, employ popup features to entice interaction, and even send and receive direct messages on social media. Certain qualities, such as their 24/7 availability and prompt replies, may help to explain why financial organizations are using chatbots to offer customer service. Adoption may also be motivated by cost reductions for these institutions. For instance, statistics indicate that as compared to customer service models that use human agents, chatbots save $8 billion annually or almost $0.70 for each customer encounter.

Since they first entered the financial industry almost ten years ago, chatbots have become increasingly popular. Today, the majority of the sector at least employs straightforward rule-based chatbots that use either decision tree logic or databases of keywords or emojis that set off pre-programmed, constrained responses. These chatbots are often driven by exclusive third-party technology firms. For JPMorgan Chase and TD Bank, for instance, Kasisto offers conversational, money-focused chatbots, while Interactions serves Citibank.

As the use of chatbots has increased, some companies, like Capital One, have developed their own chatbot technologies by using real customer conversations and chat logs to train algorithms. Capital One released Eno, a text messaging chatbot, in March 2017. Capitol One claims that Eno, like other banking chatbots, can do things like monitor account balances, recent transactions, and available credit; pay bills; activate, lock, or replace a card; and keep track of when payments are due. By the fourth quarter of 2022, nearly 32 million users will have had more than a billion exchanges with Erica.

In Q1 2023, for instance, Goldman Sachs‘ chief information officer suggested that the bank’s engineering staff start creating its own “ChatGS” or LLM chatbot to help the bank’s employees store knowledge and respond to important customer questions immediately. Financial institutions have only lately begun to implement cutting-edge technologies like generative chatbots and other products billed as “artificial intelligence.”

The industry has improved its use of chatbot technology by, in certain cases, depending on the biggest technological corporations for datasets or platforms. For instance, Truist announced its digital assistant in Q3 2022, built on top of Amazon Lex, an AWS product. Wells Fargo announced the launch of Fargo in Q3 2022, a new chatbot virtual assistant using Alphabet’s Google Cloud platform that will use LLMs to process customers’ input and offer tailored responses. Additionally, Morgan Stanley announced that it is testing a new chatbot that is powered by Microsoft-backed OpenAI’s GPT 4 technologies.

The capabilities of chatbots go beyond text messages. Consider the U.S. In June 2020, Bank released Smart Assistant through a smartphone app. Like other banking chatbots, Smart Assistant adheres to simple rule-based functionality designed to perform daily banking tasks, such as locating users’ credit scores, transferring money between accounts, contesting transactions, and facilitating payments to other users through Zelle. Smart Assistant responds primarily to voice prompts and accepts text inquiries as a backup option.

Many financial institutions are now using rule-based chatbots that are supported by social media sites as well. The majority of the top 10 banks in the US allow business chat and direct communications on either Twitter or Meta’s Facebook and Instagram. The Business Chat on Facebook and Instagram, among other things, generates automatic answers.

Problems consumers encountered while engaging with chatbots

Sectors all around the economy are increasingly transitioning from human help to algorithmic support, just as how customer service changed decades ago from in-person to distant contact centers.

Public complaints about consumer financial services and products are gathered by the CFPB. As financial institutions employ chatbots more often, complaints from the general public outline problems consumers encountered while engaging with chatbots more frequently. These problems may raise concerns about whether current laws are being followed. Below, we include some of the difficulties encountered by consumers as described in CFPB complaints. We also look at problems that chatbot adoption has created for the whole industry.

Read: Most Trending Crypto Wallet Of 2023 – Phantom

Limited ability to solve complex problems

The phrase artificial intelligence, or “AI,” is used to imply that a consumer is interacting with a highly complex system and that the answers it produces are actually accurate and intelligent. However, “AI” and automated technology may take many different shapes. People could really be interacting with a very simple system that is just capable of fetching and repeating basic information or sending users to FAQs or regulations. Chatbots should not be used as the main method of customer care when “AI” cannot grasp the customer’s request or when the customer’s message conflicts with the system’s programming.

Difficulties in recognizing and resolving peoples’ disputes

Financial institutions are trusted by the public to promptly and accurately recognize, investigate, and settle problems. Entities must correctly recognize whether a customer is voicing a complaint or a dispute since it is part of these consumer expectations and regulatory duties. A degree of rigidity may be introduced by chatbots and carefully scripted customer service agents, wherein only certain phrases or syntax may signal the identification of a problem and launch the dispute resolution procedure. As a consequence, it’s possible that chatbots and scripts won’t be able to recognize a conflict.

Even when chatbots can recognize that a consumer is raising a disagreement, there can be technological barriers preventing them from investigating and resolving it. Customers may dispute purchases or inaccurate information. Chatbots that are only capable of repeating back to customers the same system information that they are seeking to dispute are inadequate. Such echoing back does not effectively address issues or questions.

The fact that rule-based chatbots are designed to receive or process user-provided account information and cannot reply to requests that fall outside of their data inputs makes them one-way streets as well. Because the technology has only been trained on a small number of dialects, it can be challenging for customers with varying linguistic demands to utilize chatbots to get assistance from their financial institutions. This is especially true for those who speak English as a second language.

A chatbot with limited syntax can feel like a command-line interface where customers need to know the correct phrase to retrieve the information they are seeking. Going through the motions of a simulated discussion, although being touted as more convenient, may be tiresome and opaque in comparison to exploring material with simple and logical navigation.

Providing inaccurate, unreliable, or insufficient information

The repercussions of being incorrect may be severe when a person’s financial life is at stake, as is shown in more detail below. Chatbots sometimes provide the incorrect response. When financial institutions use chatbots to provide customers with information that must be accurate under the law, getting it incorrect might be against their duties.

Particularly, sophisticated chatbots that use LLMs may struggle to provide information that can be relied upon. The underlying statistical approaches are not well-suited to discern between factually valid and erroneous data for conversational, generative chatbots trained on LLMs. Because of this, these chatbots could use datasets that include examples of false or misleading information, which are subsequently duplicated in the material they produce.

Chatbots may provide erroneous information, according to recent research. For instance, a comparison study of Alphabet’s LaMDA, Meta’s BlenderBot, and Microsoft-backed OpenAI’s ChatGPT revealed that these chatbots frequently produce inaccurate results that are undetectable by some users. Recent tests of the Alphabet’s Bard chatbot revealed that it also produced fictional results. Additionally, a recent study revealed that Microsoft-backed OpenAI’s ChatGPT can exacerbate biases in addition to producing inaccurate results.

Users are asking generative chatbots for financial advice, despite the fact that they can be inaccurate. For instance, according to a survey, people use LLM chatbots to get recommendations and advice on credit cards, debit cards, checking and savings accounts, mortgage lenders, and personal loans.

The goal of using chatbots in banking is to provide consumers with quick assistance with their problems. Customers could have no other options if a chatbot is supported by faulty technology, erroneous data, or is nothing more than a portal into the business’s open policies or FAQs. For financial institutions, it is essential to respond to customers’ questions about their financial life in a trustworthy and accurate manner.

Failure to provide meaningful customer assistance

Automated replies from a chatbot could not be able to assist a client with their problem and instead drag them around in endless loops of repetitious, useless language or legalese without providing an exit to a real customer support agent. These “doom loops” are often brought on when a customer’s problem is beyond the chatbot’s scope, preventing them from having a thorough and maybe required interaction with their financial institution. As mentioned previously, some chatbots use LLMs to produce answers to frequent client questions. While some individuals may be able to use a chatbot to acquire an answer to a particular question, the same technology might make it difficult to get a precise and trustworthy response.

Financial organizations could claim that automated processes are more effective or efficient because, for instance, a person might get a response right away. Automated answers, however, may be heavily scripted and sometimes just point consumers to long policy statements or FAQs, which, if they do include any information at all, may not be particularly useful.

These systems may just be shifting to a less expensive automated procedure the obligation of skilled customer service representatives or the stress of a person needing to explain such rules. As a consequence, a number of clients have complained to the CFPB about chatbots trapping them in “doom loops”.

Hindering access to timely human intervention

Chatbots are often unable to substantially customize services for distressed consumers since they are intended to handle certain tasks or obtain information. Customers may experience anxiety, tension, confusion, or frustration when they seek help with financial issues. The restrictions of a chatbot may prevent the client from accessing their essential financial information and raise their irritation.

Research has shown that when individuals feel worried, their attitudes toward risk and choices change. One study, for instance, indicated that after interacting with a chatbot, 80% of customers felt more annoyed and 78% felt the urge to speak to a human.

Additionally, clients may not be aware of the limitations of these chatbots or the absence of a real customer support agent when they first decide to establish a connection with a certain financial institution. It won’t become obvious until a problem arises and consumers are forced to spend time and energy trying to fix it, which wastes their time, limits consumer options, and undercuts financial institutions that are attempting to compete by making substantial and efficient customer service investments.

Advanced technology deployment may also be a deliberate decision made by organizations looking to increase revenue or reduce write-offs. Indeed, the likelihood of charge waivers or price negotiations may be lower for sophisticated technology.

Technical limitations and associated security risks

Reliability of the system and downtime

At a high level, how a company decides to prioritize features and allocate development resources has an impact on how reliable automated systems will be. For instance, enhancing automated systems’ capacity to recommend pertinent financial goods to a given consumer based on their data may be of more importance in order to boost income. This investment could come at the price of functions that don’t increase sales. Therefore, even if an automated system is adept at managing certain client duties, it could struggle with others.

Chatbots may also malfunction, just like any other piece of technology. People can be trapped with little to no customer care if a malfunctioning chatbot is their financial institution’s sole option for providing time-sensitive assistance. We may see some of the chatbots’ technological limits through customer complaints, for instance.

A disappointed consumer just sees a non-functional chatbot, regardless of whether it is a programming or software problem.

Threats to computer security from spoofing and phishing websites

Because they are automated, chatbots are often utilized by criminals to create phoney, impersonation chatbots that carry out mass phishing assaults. Conversational bots often appear as “human-like,” which might make users think more highly of themselves and divulge more information than they would in a straightforward online form. When consumers provide these impersonator chatbots with their personal information, it becomes rather risky. Scammers are increasingly preying on users of popular messaging services to get their personal or financial data in order to fool them into paying fictitious fees via money transfer apps.

Chatbots may be trained to phish for information from another chatbot in addition to utilizing impersonating chatbots to hurt customers. Chatbots may be programmed to adhere to specific privacy and security protocols in these circumstances, but they may not be able to identify and react to attempts by scammers to phish for personal information or steal peoples’ identities. They may also not be programmed to detect suspicious patterns of behavior or impersonation attempts.

For instance, in Q2 2022, fraudsters pretended to be DHL, a corporation that provides fast mail and package delivery services and sent victims to a chatbot to ask for extra shipping fees in order to get products. Due to the inclusion of a captcha form, email and password questions, as well as a picture of a damaged shipment, the chatbot dialogue seemed to be legitimate.

Keeping personally identifiable information safe

Regardless of the technology employed, financial institutions are required to keep personally identifiable information secure. Security researchers have highlighted a number of potential chatbot vulnerabilities, from entities using antiquated and insecure web transfer protocols to consumers entering personal information when they are in need of assistance.

For instance, users are often asked to provide personal data in order to verify that they are the owner of a certain account. Customers expect a corporation to handle their personal and financial information with care and with confidence when they provide it to them. As a result, chat logs that include personally identifiable information from consumers should be treated as sensitive consumer information and maintained safe from hacking or intrusion.

Chat logs provide a new entry point for privacy violations, making it more difficult to completely secure the security and privacy of customers’ personal and financial information. Inbenta Technologies was used by Ticketmaster UK in 2018 for a number of services, including a “conversational AI” on its payments website. 9.4 million data subjects were impacted by the intrusion, which included 60,000 unique payment card numbers when hackers attacked Inbenta servers.

Privacy violations may occur when training data contains personal information that is then directly disclosed by the model without the consent of the individual affected. Some of these risks appear to be recognized by financial institutions, at least as it pertains to their internal information, as several large banks have restricted use.

For AI systems like chatbots, comprehensive security testing is required. This testing must be rigorous, and any third-party service providers participating in operations must be thoroughly audited. Without adequate safeguards, there are just too many weaknesses for these systems to be trusted with sensitive client data.

The CFPB’s consumer complaints about chatbots raise questions about whether using chatbots prevents institutions from safeguarding the security of customer data.

The perils of implementing flawed chatbots

Financial institutions should take into account the technology’s limits, such as those described in this research, as they continue to invest in tools like chatbots to manage customer service while also cutting costs. Risks associated with using chatbot technology as the main method of communicating with people include the following for certain financial institutions:

Possibility of breaking federal consumer financial regulations

Federal consumer finance regulations that were approved by Congress impose a range of pertinent requirements on financial firms. These requirements, among other things, include giving clients honest responses, which helps to guarantee that financial institutions treat customers fairly.

Financial institutions bear the danger that the data chatbots give may not be correct, the technology may not recognize when a client is claiming their federal rights, or it may fail to secure their privacy and data when chatbots ingest user messages and respond.

When chatbots replace humans, customer service and trust suffer.

Consumers may have urgent needs when they contact their financial institution for assistance. Their confidence and trust in their financial institution will decline if they get bogged down in loops of monotonous, useless language, are unable to activate the proper rules to receive the answer they want, and are not able to speak with a live customer support agent.

People may not have much negotiating power when a supplier is chosen for them, given the nature of the marketplaces for many consumer financial goods and services. For instance, choosing a mortgage servicer or credit reporting agency offers little to no customer choice. Additionally, even in marketplaces where customers have more options, financial institutions may not fiercely compete on key aspects, such as customer service, because clients are only exposed to those benefits after choosing the provider and are therefore in a way tied into them.

In these situations, the potential for significant cost savings may significantly encourage institutions to direct customer care via chatbots or other automated systems, even if doing so somewhat degrades the customer experience. Importantly, the amount of cost savings that are passed on to customers in the form of improved goods and services is reduced in such marketplaces where competition is limited or absent.

Financial firms could even go so far as to limit or stop providing individualized human help. However, it is probable that trust and service quality will suffer as a result of this decline. This trade-off is particularly relevant to consumer groups like those with poor technological availability or low English proficiency when chatbot engagements have greater rates of unsuccessful resolution.

Risk of harming people

In addition to losing the confidence of customers, chatbot failures in the marketplaces for consumer financial goods and services have the potential to have far-reaching negative effects. When someone’s financial security is in jeopardy, there are significant consequences for making a mistake. It’s crucial to be able to identify and manage consumer complaints since there are occasions when it’s the only practical method to quickly fix a mistake before it leads to even worse consequences. It might be disastrous to provide false information about, say, a consumer financial product or service. It could result in the imposition of unjustified costs, which might in turn result in poorer outcomes like default, the client choosing a subpar choice or consumer financial product, or other disadvantages.

Therefore, it might be harmful for a person to ignore or avoid a conflict. It might undermine their confidence in the organization, discourage people from seeking assistance with problems in the future, lead to frustration and time waste, leave manageable problems unresolved, and have growing negative effects.

Financial organizations run the danger of offending their consumers and doing them serious damage, for which they might be held liable, by using subpar chatbots.

Conclusion

It emphasizes the danger that relationship banking faces from algorithmic banking by continuing the now-familiar theme of animosity against AI and algorithms. It’s unclear if the CFPB will really raise what seems to be customer service concerns to claimed legal breaches, despite the fact that the statement undoubtedly seems to be intended to get financial institutions to pay particular attention to the issues the bureau claims exist.

Some of the difficulties in using chatbots in consumer financial services are highlighted in this paper. There will probably be a number of significant financial incentives to switch away from the help provided in-person, over the phone, and via live chat as industries throughout the economy continue to incorporate “artificial intelligence” technologies into customer service operations.

Poor chatbots that restrict access to live, human help may result in legal infractions, reduced service, and other negative effects. The CFPB will continue to carefully examine a variety of long-term effects of the move away from relationship banking and towards algorithmic banking.

Read: What Is Data Science?

[To share your insights with us, please write to sghosh@martechseries.com]